The Coal Bet | $AMR Thesis Full Write-Up

Why I'm long Met-Coal and a full stock write up for Alpha Metallurgical Resources ($AMR) and Warrior Met Coal ($HCC)

Today, we’re gonna talk about coal.

Specifically, Metallurgical Coal or “Met-Coal” for short; also known as “coking-coal” or even more simply put: steelmaking coal. I’ll lay out my thesis for Alpha Metallurgical Recourses (ticker: $AMR), and try to explain my back of the napkin methodology for valuing this company. I’ll also say a bit about another (albeit smaller) coal position of mine: Warrior Met Coal (ticker: $HCC). I’ve spent months learning about the coal space in order to justify (to myself) this shift away from my usual circle of competence, so hopefully I can summarize what i’ve learned for you - but odds are we’re gonna get real deep, real wide, and dirty as hell. Thanks for checking out the Margin of Sanity, and (apologies in advance for this) lets dig in.

I’ll start at the beginning.

In late 2024, equities were no longer cheap as a group. Nothing I already owned (TSM, Visa, Amazon, ect) looked attractive at their present valuations. I was stuck with some cash and nothing to buy as the AI hype and moderating interest rates pushed prices for a lot of quality companies above comfortable levels. So I began looking for new ideas outside of what seemed to be a frothy mainstream market narrative, and I stumbled upon the 13f filing of a famed value investor named Mohnish Pabrai. To be clear, that 13f was comprised only of his U.S equity holdings, and didn’t include his large investments in Turkey (perhaps a subject for another day). That said, the 13f seemed to have within it a very large and growing amount of stock in a few coal producers. The largest position was a company called “Alpha Metallurgical Resources.” When I peaked at the stock chart I saw that the price had come down dramatically from its high of ~$400/share to around ~$150/share. Despite that drop, the stock was actually up over 1,000% from its inception in February of 2021. My eyebrows were raised partly because of the apparently outstanding returns of a coal mining stock, and partly because Mohnish (like myself) is a Warren Buffet disciple. This seemed like a very un-buffet type investment.

I remembered this quote from Buffet:

“In a commodity type business, its very hard to be smarter than your dumbest competitor.”

But coal is a commodity! So whats going on here? That is the very question I hoped to answer.

As a side-note, I also think its important to mention the Mohnish element because I believe in being transparent about my actual thought process and discovery methods. My goal isn’t to impress anyone, its to clearly lay out my actual ideas and my process in an honest and coherent way so I avoid fooling myself later on. This wasn’t my idea, its Mohnish’s idea. The problem is that he doesn’t talk about it very much as he is still building his positions. So I had to do the leg work; and it was lot of leg work.

Part 1: Not all coal is created equal

Coal is broadly defined as a black or brownish-black, carbon-rich sedimentary rock formed from the compression of plant matter over millions of years. Simply put, coal is a rock that burns. It burns hot and it burns long. It’s energy density (i.e, how much heat it emits over time per unit of volume) is twice that of a substance like wood. Its also easier to store and transport than wood. It contains less moister which makes it burn hotter and more consistently. Coal also produces less smoke and tar than wood which makes it a cleaner fuel source for industrial use. For energy generation this makes coal an excellent source of heat energy. But we’re not here to talk about that kind of coal.

Coal used for energy generation bares the name “thermal” coal. It can also be referred to as “newcastle” coal. But there is another type of coal which serves a very different function in our society called “Metallurgical Coal” (aka Met-coal, coking-coal, or steelmaking coal). The key difference between thermal coal and met coal has to do with the chemical composition of the rock itself. Thermal coal is comprised of a high percentage of what is called, “volatile content” - which I think of as just sort of…junk. Basically, you don’t want too much of this volatile content in your coal, but when you’re using coal to generate energy, a higher amount of volatile content is ok (although it does increase the amount of pollution generated by the burning of that coal). When converting Met-coal into “coke” for steelmaking, you definitely don’t want a lot of volatile content. If you’re converting coal to coke to make steel you want high carbon content and low volatile content. To quickly sum up, within the world of coal there are two types: coal for energy and coal for steel. You can use steelmaking coal for energy generation, but you can’t use thermal coal for steelmaking. Today we’re here to talk about Met-coal (steelmaking coal), hence the name of the company: “Alpha Metallurgical Resources.”

Not at metallurgical coal is created equal either.

I’m sorry to do this to you, but we have to explain a few more coal terms here. Within the world of steel making coal, there are two types. One is called semi-soft coking coal - which we can basically ignore today, although it is a type of steel-making coal. The other type is called hard coking coal (HCC), which is interestingly the ticker symbol for the company “Warrior Met Coal” that we will discuss later. As the names suggests, hard coking coal produces a stronger coke and therefore a stronger steel. The difference again comes down to the amount of volatile content. Hard coking coal has less volatile content and is much better for producing steel. Semi soft coal is cheaper, but must be blended with hard coking coal in order to actually be useful in steel production.

Oh right…not all hard coking coal is created equal either!!!

I promise this is the last distinction. Within the world of hard coking coal we have 4 key types that I will rank in terms of “quality”:

Low Vol

Mid Vol

High Vol A

High Vol B

Something to note is that “low vol” stands for “low volatility” and therefore “high carbon.” Remember that we don’t want volatility, right?

So: Low Vol > Mid Vol > High Vol A > High Vol B

It should be noted here that most steel makers use a blend of these types of hard coking coals. One ton of Low Vol HCC will usually fetch a somewhat higher price than High Vol A or B, but they are all needed for the worlds steel production and therefore usually move more or less in line with one another in price.

In summary, when it comes to met-coal its all about the carbon and avoiding the volatile content.

Less volatile content = more carbon = stronger coke = stronger steel.

One final note is that generally speaking met coals are blended. Using only a very low vol coal is actually not very ideal or cost efficient. That said its still sort of “the good shit.”

If you’re still confused i’d suggest going back and re-reading to get all that straight in your head before we press on. If you’re listening on a podcast player, this write up is available for free on the Margin of Sanity substack.

Ok, moving on.

Part 2: A “Brief” Summary of Steel

Technically speaking, steel has been around for 3,000 years. Steel is essentially just an alloy consisting of iron ore and carbon. In the early days it was produced unintentionally by iron workers smelting their iron in charcoal-rich furnaces. The iron ore would absorb the carbon from the charcoal that was being used to heat it, and you’d end up with steel. As early as 1200 BCE, ancient metalworkers in regions around Asia-minor and India began producing this new metal alloy deliberately, and by 300 B.C Indian artisans had perfected the art of producing something called Wootz steel. Jump cut to the mid-evil period and we have blacksmiths producing steel in small forges to produce stronger weapons and tools. Centuries pass, kingdoms rise and fall, and we end up in the new world called America where we meet a man called Henry Bessemer. In 1856, Mr. Bessemer patented something called “the Bessemer Process” - a new way to produce steel on an industrial scale. The process employs use of a “blast furnace” to…well…blast air into molten iron ore that has been heated by carbon rich coal. You may not have heard of Bessemer, but you probably know the man who took his idea of the blast furnace and scaled it to a size beyond imagination at the time. Andrew Carnegie, seeing America’s need for mass construction of bridges, railroads, ships, skyscrapers, and all sorts of tools and machinery, took Bessemer’s process for producing strong and cheap steel en-masse and gave birth to Carnegie Steel; today the company is called U.S Steel.

Steel itself serves an irreplaceable and invaluable role in our modern world. It is quite simply the backbone of modern life. We use it to build bridges, roads, railways, buildings, beams, pipelines, tunnels, dams, cars, trucks, buses, trains, planes, stadiums, ships, hand tools, power tools, plows, troughs, harvesters, cranes, bulldozers, drills, furniture, kitchen ware, wind turbines, oil & gas rigs, nuclear plants, solar mounting systems, weapons, and even refrigerators.

In short, if you want to have a society that looks anything like a modern civilization, you need steel….you need a LOT of steel.

Methods for steelmaking today

We spoke earlier of Bessemer and his blast furnace. The blast furnace method of steel is still the dominant method of steel making in the world. About 70% of global steel production is “virgin steel” produced in a blast furnace using a blend of met-coals and iron ore. In the U.S, however, about 70% of our steel production is actually recycled steel made in something called an “Electric Arc Furnace” (EAC). There is a third method of steel-making that uses hydrogen, but its basically not worth talking about as it it currently produces less than .1% of global steel and is not only logistically daunting to produce at scale, but it is arguably also quite dangerous (water in a blast furnace = boom). So we’re left with virgin steel forged in blast furnaces, and recycled steel made from scrap in an electric arc furnace - which use ~30x less met-coal than a blast furnace.

Recycled Steel in Advanced Economies

The U.S has been shifting away from blast furnace made virgin steel and towards recycled scrap steel for decades. In the year 2000 it was almost 50/50 virgin steel to recycled scrap. As I mentioned earlier, 70% of U.S steel production is recycled scrap. As you might have guessed, we are only able to do this because we already produced so much steel in the previous century as U.S industrialization transformed farmers to factory workers, horses to automobiles, and villages into skyscraper dense metropolises. Recycling steel has been a somewhat easy choice to make as it is both cheap and green. Of course, steel recycling at scale is less realistic in less advanced economies, but we will get to that. For now lets stick with the U.S and take a look at the two main challenges of steel recycling at home:

Scrap steel just ain’t what it used to be. And I mean that quite literally. The makeup of recycled scrap steel is not the same as that of virgin steel. Materials like copper, tin, and other residuals mix in with the steel and weaken it. Thats no big deal if you’re using rebar to re-enforce a road, but its a big problem if you’re building a skyscraper or an airplane. Recycled scrap steel is fine for some things, but needs to be re-enforced with virgin steel for others.

Steel lasts for a long time, and so do the structures it supports. When you use scrap steel (or virgin steel) to build a road, a building, a bridge, a dam, or even something like a cargo ship, the steel ends up staying out of circulation for as long or longer than that thing you used it to build. Infrastructure (like the kind built under the IIJA (infrastructure investment and jobs act), takes steel and pulls it out of circulation for 50-100 years. Unlike automobiles which might have a life cycle of 10-20 years, infrastructure being built in America today may very well create a shortfall of scrap steel supply by 2030. To make up for that demand we must produce more virgin steel. When you apply population growth and continued industrial development to this sort of reasoning, you end up concluding what I did; we’re gonna need more steel.

Ok, so thats the U.S. Who else needs a lot of steel?

Part 3: China

Over the last two decades the story of China’s growth has dwarfed anyone’s expectations in terms of its size and speed. The country’s 1.4 billion people have experienced an immense shift from a largely agrarian life to a modern industrial one. This impressive growth and development of China’s economic makeup has been built on the scaffolding of infrastructure, manufacturing, and housing. Bridges, rails, roads, and massive skyscrapers enable both mobility and the development of megalopolises that must house tens of millions of people. Much of China’s population now works in a booming industrial manufacturing sector that employs the use of machines built using steel, in factories made with steel beams and steel re-enforced concrete, transported by steel framed automobiles or steel train cars on steel train tracks, over bridges and through tunnels who’s frames and support beams are also made of (yup) steel. China’s steel production has risen from a 15% share of global steel production to 50% in more recent years. It is the growth of China which has driven the demand for steel in the world over the past two decades, thereby also driving the demand for virgin steel made using metallurgical coal. In 2023 alone China produced about 1 billion metric tons of steel, 90% of which was virgin steel produced in a blast furnace using ~780 million metric tons of met coal. For context, that is 2,327 Empire State buildings worth of met coal consumed in China in 2023.

Now is a good time to mention that many people believe this sort of eye-watering growth in China is slowing or even coming to an end. Debt, deflation, and demographics weigh on a nation that has significantly over built its housing sector. Overbuilding of housing is a hard hurdle to overcome quickly. We’ve all probably seen pictures and read articles about massive empty apartment buildings filling the skylines of Chinese cities. But in 2023 China was still red hot, and as a result of this ever-surging demand for met coal, prices for 1 metric ton of “Premium Low Vol” met coal had reached over $300/metric ton. As of today that same metric ton is bought and sold for ~$180/mt. It should be noted that there are plenty of other external factors which influence the price of any commodity (met coal is no exception), but its the cooling of China’s growth which is undoubtedly behind the cooling of demand (and price) that i’ve just mentioned. Its anyones guess as to the future of Chinese steel production and consequent demand for met coal, but current met-coal prices have a subdued China baked into them. Of course things could get worse, but renewed demand in China is not a necessary component of the met-coal thesis.

Lets back up.

Perhaps you’re wondering, with all this steel production in China over the years, wouldn’t they just mine their own met-coal? Isn’t this obscenely long write-up ultimately about a U.S coal miner? Why are we talking about China at all?

Well as I said earlier, not all coal is created equal, and China ain’t got the good stuff.

Coal reserve formations are millions of years old, and whether a country’s borders contain thermal coal, semi-soft, High-Vol A/B, or Low-Vol is purely luck of the draw. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that China drew the short straw here, but more that Australia drew the longest; and the U.S isn’t far behind. China’s domestic met-coal supply contains mostly thermal coal, semi-soft coking coal, and some of the lower carbon (higher volatility) hard coking coals. China needs to blend those lower carbon coals with imported higher carbon “low-vol” coking coals to produce decent steel. That high carbon “premium low vol” coal is littered throughout Australia, as well as in one particular region of the United States known as Appalachia - coal country. And it is in that region of the U.S that both companies we will discuss mine their coal.

Canada’s British Columbia also contains a fair bit of low vol coking coal, but Canada primarily exports to East Asia, and that region is not where I see the future of met-coal demand arising. Which brings me to….

Part 4: India

India’s population is roughly the same as China, but India’s growth has been far slower than that of China in recent years. There are 1.4 billion people in India who are equally in need of the cars, bridges, roads, skyscrapers, factories, ect that the equatable population of China has enjoyed throughout the beginning of this century. Unlike China, however, India does not face such daunting demographic problems. Birth rates are not a problem in India. The Indian Government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is moving ahead on any and all economic and infrastructure related spending it can.

"India will run towards development at breakneck speed... Today, India is the 5th largest economy in the world. It won't be long before we become the 3rd largest."

-Narendra Modi (Prime Minister of India).

In 2021, Prime Minister Modi announced a 1.35 trillion dollar (not rupee) infrastructure plan. The nation of India has the will, the people, the leadership, and the financing to grow its economy to where it belongs on the global stage. The one thing it doesn’t have is hard coking coal.

Yep, India’s natural coal reserves are even less suited to steel production than China’s. As a result it must rely primarily on imported HCC (hard coking coal) from nations like Australia and the U.S to feed the many blast furnaces which will forge their future prosperity. India’s blast furnace capacity is rising year on year in the mid double digits as the country prepares to continue ramping up its steel production. So it will be India, not China, driving demand for met coal over the next decade.

Australia vs The U.S.A

And the winner is….Australia. Lets just get that out in the open really quick. As a yankee doodle myself I wish I had a great case for U.S dominance in met-coal exports, but it just ain’t so; at least not for a while. A quick look at a map and you’ll notice Australia is quite a bit closer to the Indian subcontinent than good old West Virginia. As a result, Australian coal has a natural advantage in sheer transportation cost savings. Plus, the Australians just happen to have a ton of high quality coal.

I should mention here that while Australia has been the dominant producer of met coal, they expect a LOT of mine closers between 2027-2029. Australian met-coal exports are expect to grow slightly in 2025-2026 to 174 million tons, but then fall to 159 million tons by 2030. Production decline estimates are entirely related to the 24 mine closers expected between 2027-2029. That said, Australia is still the king of the hill as far at met-coal is concerned.

In 2016 Australian met coal made up 85% of India’s coking-coal imports. In 2023 that number had dropped to “only” 53%. This drop in market share for Australian coal is not a coincidence. Now that you understand how important steel is to an economy, you may also begin to imagine why met-coal is equally as important. India’s over reliance on Australian coal imports poses an intrinsic risk to their economy. Mine fires, floods, shipping delays, trade wars, or even just mine depletions threaten to cut off India’s supply of met-coal (and therefore steel). In order to mitigate this risk, India has begun to ramp up coking coal imports from other nations - the U.S.A being chief among them. As of 2024 the U.S share of India’s met-coal imports has grown to 14.5% from 3% in 2016.

In third place is Russia (10% share). While Russia does in fact produce a large amount of PLV, they lack sufficient quantities of High Vol A/B needed for blending in Indian blast furnaces. Another issue is logistics. Rail congestion in Siberia and the Russian Far East (Trans-Siberian and Baikal–Amur Mainline) severely limits throughput. On top of that there is limited port capacity at key eastern export terminals like Vanino, Nakhodka, and Vostochny. These terminals are shared with thermal coal exporters, causing delays. Sheer distance is also a logistical disadvantage. The distance to India is longer than from Australia or even the U.S. East Coast (via the Panama Canal or Cape of Good Hope). Moreover, bulk shipping is used to transport Russian coal to India, but the issue of lack of return freight makes this a more expense “one way” type operation. Russia may send coal on bulk carriers to India, but those same ships don’t have anything to bring back to Russia since Russian imports from India largely consist of light weight goods transported on cargo ships. Add sanctions and concerns over contract enforcement to this mix of problems, and Russian coal stops looking very attractive to Indian buyers.

In the end price is still the key factor. Indian steel makers aren’t really going to pay up for diversification - nor should they. Fortunately, the supply for HCC is somewhat limited, and so as India’s growth ramps up, so will the price for high grade met-coal. When met-coal prices are in the toilet, the cheapest producers win 100/100 times. In that sort of environment, it is the Australian producers that can compete on price because their costs are fundamentally lower than U.S producers. Its not that U.S producers won’t sell - its that they’ll be forced to sell at a loss. That dynamic has already begun playing out recently as prices for met-coal have indeed taken a beating in the past year. But as prices rise with renewed demand in India, the playing field begins to level, and suddenly U.S met coal producers are profitable. At the prices U.S coal producers sell for today, a little profitability goes a long way.

and so finally we arrive….

Part 5: Alpha Metallurgical Resources ($AMR)

Headquartered in Tennessee, Alpha Metallurgical Resources is the largest U.S producer of coking-coal. Alpha Met is also a pure play met coal producer and no longer has any thermal coal operations to worry about. AMR has virtually no debt and nearly $500 million in cash sitting on their balance sheet. Their market cap is a mere $1.6 billion, putting their enterprise value at 1.1 billion. About 70% of their revenue comes from exports and the remainder is domestic sales. Unlike many other miners i’ve looked at, Alpha Metallurgical Resources is not only a pure play met-coal company, but they have no new mines or large cap-ex endeavors to spend their cash on. Instead, management chooses to return cash to shareholders in the form of buybacks (my favorite). In 2022 and 2023 the combined spend on share buybacks was a whopping 1.06 billion. You read that right…the current enterprise value is nearly equal to just those 2 years of buybacks. Before we get overly excited I have to point out that those were two exceptional years for met-coal prices. In no way am I suggesting that they will be able to sustain near that level of buybacks every year, and as a matter of fact the buyback spend for 2024 was significantly lower at a mere 38 million. As China has slowed down and coal demand has cooled with it, AMR’s management is choosing to move forward with caution…

….$500 million in cash worth of caution - which brings me to a quick but important aside….

Cash is the only good option and I love it

One of the reasons I almost always avoid miners is debt, capex, and the misguided use of both. As prices for a commodity increase, managements often pull on credit markets to fund new operations. Those new operations create over supply which creates downside to price which effectively makes the return on that capex spend far less profitable than what was promised to shareholders. The debt stays on the balance sheet and interest payments eat away cash flows while depreciation weighs on earnings. Its not called a cyclical business for nothing!

Fortunately, thanks to ESG constraints, financial institutions have faced significant pressures to stop lending to “dirty” businesses like coal miners. This trend explains the many spin-offs of coal operations from some of the larger mining companies - Teck-Resources, Adaro Energy, and Anglo-American have all spun off their coal businesses in the past five years.

The consequences of this shift away from coal are three-fold and all are good for AMR:

AMR can’t use debt so it must hold cash and frankly thats the sort of balance sheet I prefer anyway! - especially in a higher interest rate environment.

Smaller and less well capitalized coal miners are going under and that will weaken supply; thereby setting up a situation where increased demand will push up price rather than serving as a catalyst for new supply to come online.

Many institutional investors are restricted from buying stock in coal miners, and so AMR can buy back its stock at a cheap price somewhat indefinitely.

Lets quickly look at some figures. As of today AMR’s market cap is $1.6 billion with about $500 million in cash leaving an enterprise value of 1.1 billion.

In 2020 net income was a loss of $121 million

In 2021 net income was $289 million

In 2022 net income was $1.45 billion

In 2023 net income was $722 million

In 2024 net income was $187.6 million

AMR’s earnings are tied entirely to the price of met-coal which is subject to large swings. 2024 was not a great year for coal prices as the world’s largest steel producing economy (China) slowed down. Still, AMR managed to show a profit of $187.6 million (although the price of met-coal was still sliding throughout the year).

AMR currently has 13.05 million shares outstanding putting their 2024 EPS at $14.37/share. Their enterprise value/share is currently ~$84/share. That leaves an EV per share/Eps ratio of 5.84. (I realize that is not a common figure to quote, but its just a P/E after factoring in cash.)

To me, thats cheap considering the prior year’s net income divided by current share count would make EPS 55.32 (more than half of the current EV/share). I could do the same math for 2022 when they earned $1.45 billion (well over their current total EV), but considering that was such an exceptional year for met-coal prices I think its best to stick with less exceptional numbers.

Lets dig into AMR’s mix of coal grades, costs, and realized prices/ton.

Not all coal is created equal right? Well, of the 14.6 million tons of coal they produce each year, here is a rough breakdown of the different types of coal grades.

High-Vol A (HVA) ~25–35%

High-Vol B (HVB) ~20–30%

Mid-Vol (MV) ~20–30%

Low-Vol (LV / PLV) ~10–15%

Yeah its not what I hoped for either… PLV isn’t the dominant coal type AMR produces, but that is changing somewhat. In the back half of 2025 AMR’s Kingston Wildcat mine is expected to begin producing 1 million tons of PLV per year over a mine life of about 11 years, thereby increasing the PLV share of production by ~7%. All in all AMR produces a good mix of quality coking coal; making them a perfect supplier of India’s growing need for met-coal. Later on we will discuss Warrior Met Coal who does fit the bill as a PLV powerhouse. But first lets talk about AMR’s costs and realized sale prices.

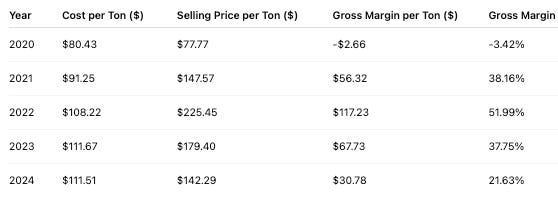

Here is a table showing production costs per ton, selling price, and gross margin:

Costs per ton seem to have stabilized by now, but as you can see inflation and increased freight costs pushed them up from where they sat mid-covid. I’d say a cost of $111/ton is overall a fair enough estimate to use going forward. AMR is not the lowest cost producer of met coal in the U.S, but they are the largest. The sheer number of tons mined per year (14-15 million), means that as coal prices rise, AMR will benefit most. I think of this as a form of operating leverage. AMR produces 14-15 million tons of met coal per year, and as the unit price rises for each ton sold, all of that extra cash flows straight through to the bottom line. Since management has shown that they are eager to return all of that cash back to shareholders in the form of buybacks, its hard to see a world where AMR cant produce its market cap in free cash flow fairly quickly in a good market. However, that lovely operating leverage I spoke of cuts both ways. Since rolling back or halting production is far from ideal (or cheap), when coal prices fall below profitable levels AMR must also sell more coal at a loss than anyone else (in the U.S anyway). Perhaps now you’re understanding why most of this article has been an explanation of supply/demand dynamics in met-coal rather than a lengthy cash-flow statement analysis.

AMR is well positioned to benefit most from a surge or even just modest rise in the price of coal over any period. Their production volumes, coal blends, and fortress balance sheet are not reflected in the current market valuation of $1.6 billion ($1.1 billion EV). To this investor, that price looks dirt cheap - Mohnish Pabrai paid an average price of $183/share and today AMR is selling in the ~$120/$130 range. My average purchase price is around $140/share.

Part 6: Warrior Met Coal ($HCC)

On my hunt for new ideas, I couldn’t help but notice another pure-play met coal producer in Pabrai’s portfolio. If you hadn’t already connected the dots, Warrior Met Coal’s ticker symbol, “HCC,” is a nod to their core business of mining and selling Hard Coking Coal (HCC). Warrior’s market cap (~2.5B) is larger than AMR’s despite producing about half the tonnage of Alpha-met in a given year. Warrior has about the same amount of cash on their balance sheet as AMR (~$500m), but that must be considered against their total debt of $172 million (remember AMR is basically debt free). Another key difference is the relative lack of capital returns to shareholders compared to the monster buybacks employed by AMR’s management. The reason behind this difference is the substantial amount of cap-ex that has been needed to fund their Blue Creek mine; set to begin production in 2025 and ramp to 2.7 million tons/year in 2026 with production stabilizing at 4.4 million/year by 2027). While I basically avoid most capital intensive businesses, most of the capex needed for Blue Creek has already been spent with another ~$300 million more needed to complete the project. So far I doubt any of you are getting very interested in Warrior what with their lower tonnage, weaker balance sheet, and future cap-ex requirements. You may also ask why their market cap is $2.5 billion compared to AMR’s $1.6 billion. Some of this can be explained by a song you’ve heard me sing before…

Not all coal is created equal…again.

Warrior met coal may produce half the total met-coal churned out by Alpha Met in a given year, but the coal they do sell is PLV and Mid-Vol; which they produce for a lower average cost per ton than Alpha-met. I should re-iterate that its hard to say one type of coal is objectively "better” than another since most steel is produce with a blend of different coal types, but if there was a winner it would be PLV with Mid-vol in second place. Those are precisely the two types of coal Warrior produces. These coal types are simply more rare to find in large quantities these days (particularly within the borders of countries that really need them) - and they fetch a premium on the market compared to the more common HVA/HVB coals. Warrior’s smaller scale may seem like an objective negative, but that also means that they lose less money in weak met-coal markets. Selling more of a finite asset like met-coal at a loss is… not a good thing. Alpha-Met may win bigger in up markets, but they also suffer more in weak ones. Moreover, Warrior produces coal for about a 10% lower cost/ton than Alpha Met. The lower production costs together with the premium prices HCC receives for its coal mean that their business is more resilient in the tougher times. Alpha Met may be a winner in an open battlefield while the sun shining, but Warrior can fight in the mud. At present, what with China’s economy faltering and a looming tariff slowdown, the met-coal market is looking a bit muddy. Investors also likely believe that once Blue Creek is operational, Warrior’s management will turn their attention towards AMR-type buybacks. I took a position in Warrior as a bit of a hedge, but its still only about 1/4th the size of my Alpha-Met position. In the end I think both are significantly undervalued.

“Conclusion” (yes, finally)

In the short term its hard to say precisely what will happen to the price of met coal, but in the longer run I think the picture is more clear. Supply is constrained by lack of new investment in high quality met-coal mining, and the nations that need that coal aren’t the ones producing it. The negative drag on virgin steel production in the U.S caused by the recycling of scrap steel is mostly behind us as we bury much of our scrap steel into large scale infrastructure projects. China may stay cool for a while, but India is just getting started. As Australian miners shutter their doors in the back half of the decade, U.S miners like AMR and Warrior will be poised to capture a greater share of the global market - at higher prices than we see today. At their current valuation both AMR and Warrior are cheap if you’re comfortable holding through some uncertainty and potentially greater declines in coal prices in the short term. As long as valuations for AI/chip/datacenter driven equities remain optimistically priced, i’m always looking for value in unloved or even hated industries like coal. Most people hear “coal” and they think of a rusty old power-plant polluting our Earth with a dying fuel source. As long as Alpha-Met is buying back their shares, I say let them.

Finally, I have to give some credit where credit is due. While I struggled to get my mind around this industry I found one very helpful source of expertise from a fellow named Matt Warder at “The Coal Trader” Substack. I’ll drop a link to check that out below.

Thanks for reading and please drop a like or comment if you found this write up helpful. I find writing up my investment thesis helps me so much, and i’m hoping it helps you too if you’re out there like I was digging for coal.

Hey Wouter! Glad you enjoyed it. AMR's price may not be at its exact bottom, but its certainly pulled back a LOT. NRP may be an overall safer bet, and i'm not so sure I have some excellent argument against NRP. They do seem to pay a dividend and I prefer AMR's buyback emphasis. NRP is basically just a royalty collector on the coal harvested from their land. Six Bravo has a good couple write ups on NRP and if suddenly I couldn't buy AMR I would happily buy NRP. Valuation is tricky with a miner. Its not like other companies since the swings in prices of their "product" are totally out of the companies hands. I do believe AMR has more upside potential in a hot coal market than NRP, but NRP has a more stable business (for a while anyway). I would do a lot of digging (pun intended) on both companies before investing. I can't tell you precisely what a good moment to "get in" is? I've been buying, but with the knowledge that I may have to wait a year or two before we see any recovery in coal prices. The thesis is very much still intact though. I would definitely advise caution with this position in particular. You have to understand it enough that you would be happy if the price dropped 25% or something and you could buy more. I hope that helps!

Hey Nishant, thanks for putting this on my radar. Looks like Accelor is still producing about 70% Virgin steel, and I'd guess in India that's closer to 90%. The interesting thing that I didn't know until just now was that these guys import met-COKE to India rather than met-COAL. Coke is the processed form of met coal that is actually used in the blast furnace. India has recently (January of 2025) implemented HEAVY restrictions on met-coke imports (a decision JV/Nippon is suing them for actually). AMR and Warrior aren't effected because they import met-COAL (cucumbers) rather than met coke (pickles). Seems like before this Accelor had also sold off their met-coal operations in Kazakhstan. Seems like the Indian government has yielded a little to Accelor (allowing another ~74k M/t of met-coke in from Poland) and they've dropped the suit. But I should point out that met-coke is made from met coal, and if Polish met coal mines (which are riddled with debt by the way) are exporting to Accelors furnaces, that means they're not exporting elsewhere, so supply isn't as effected. Since Accelor is primarily interested in steel making I don't have a problem with them being in India, especially if they end up being forced to import Met-coal by the Indian government (who cares about stability, quality, and price more than anything)